Assessing The Financial Viability Of A Business And Solvency Of A Company

Meaning of insolvency

The term ‘going concern business’ is an accounting term which assumes the subject business will continue to trade into the foreseeable future and there are no plans, events and/or circumstances which would result in that business ceasing to trade. There are many reasons why a business may cease to trade – one of those reasons could be that the company which owns the business is insolvent.

The word ‘solvency’ is defined under section 95A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) as being a company which is able to ‘pay all its debts as and when they fall due’. Therefore, ‘insolvency’ is when a company cannot pay all its debts as and when they fall due.

A forensic accountant may be called to provide an opinion on solvency or insolvency of a company and/or the financial viability of a business. For example:

- if a company is placed into liquidation, the liquidator may commence recovery proceedings against the directors of the company because the directors are personally liable for the debts of the company throughout the period of time when a company trades while it is insolvent. In this example, a forensic accountant may be required to help establish the point in time when the company became insolvent;

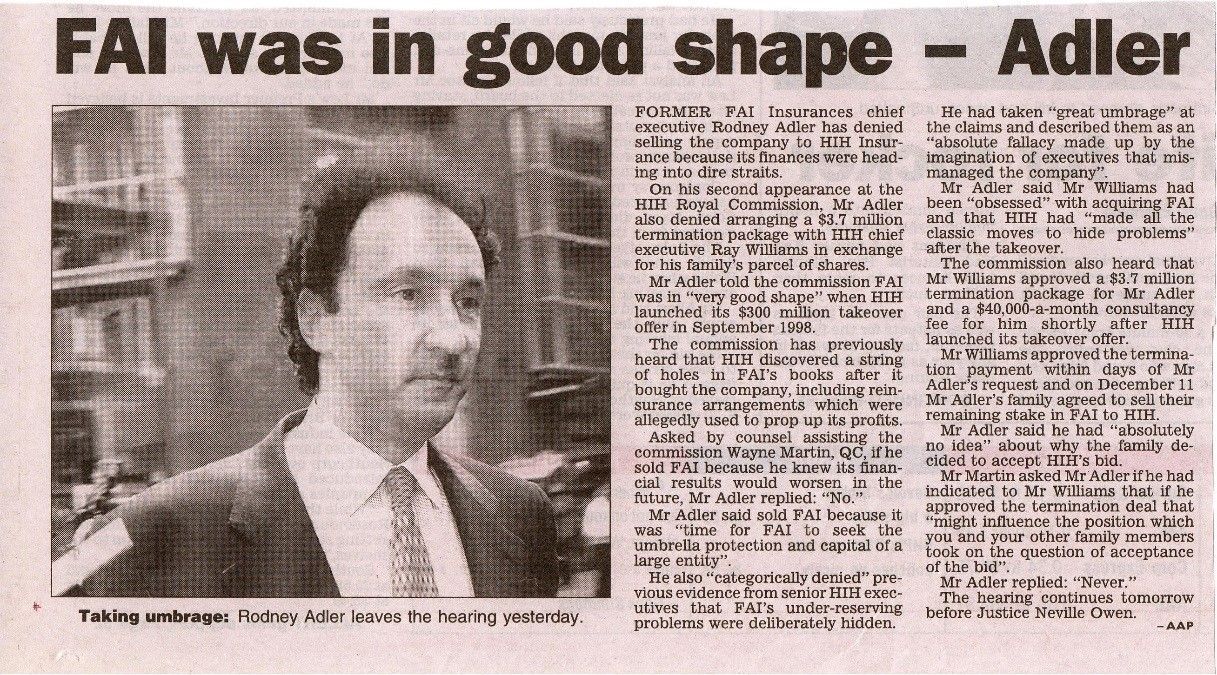

- a business was sold at a price which exceeded its value because the purchaser incorrectly assumed that a seemingly profitable business was a financially viable, going concern business. For the purposes of this article, I consider a financially viable business to be one which is able to pay its debts it incurs in carrying on its business as and when they fall due from the profits generated by the business. In this example, a forensic accountant may be called to review due diligence material and valuations relied on at the time of the sale of the business to establish a true value of the business and potentially negligence of particular parties; or

- a business is facing an existential threat, has ceased to trade or trades at a significant reduced capacity due to, say, a compulsory acquisition of land, third party breach of contract or some other wrong doing and a claim for loss is being pursued. In this example, a forensic accountant may be called to help determine whether or not the claimed losses would have been realised but for the event or opine on whether the business would have collapsed in any event.

It is theoretically possible for a financially viable business to exist within a technically insolvent company (e.g. as a result of directors of a company being negligent or reckless by not paying creditors and directing profits and cash into other businesses or companies which do not return a profit). Depending on the circumstances, the forensic accountant may need to make a distinction between a financially viable business and an insolvent company and opine on whether the business is financially viable and/or whether the company is solvent.

The following are positive indicators of financial distress faced by business and red flags that the company may be insolvent:

Poor financial position

The starting point in assessing a company’s solvency is to review the balance sheet of the company and check the net asset position. A deficit in net assets, particularly deficits observed over a period of time, with the size of the deficits growing over time represents a positive indicator of financial distress.

However, adopting this approach alone does not take into account the timing of when debts are payable and more analysis on a company’s financial position can be performed in relation to the working capital of the company. Where a company’s current liabilities (generally assumed to be liabilities due over the next 12 months) exceed the company’s current assets (generally assumed to be assets which will be converted to cash over the next12 months), the company has a deficit in net working capital. A deficient in working working capital, particularly deficits observed over a period of time, with the size of the deficits growing over time represents a further positive indicator of financial distress.

Poor financial performance

It is generally accepted by accountants that a business which has been historically profitable as determined from its profit and loss statements included in its financial reports is a positive sign of solvency as this would indicate lower financial stress to pay all debts due, compared to a business which has been reporting losses.

Historical profitability can be analysed in a number of different ways including, Earnings Before Interest and Tax (commonly referred to as EBIT), Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation (commonly referred to as EBITDA), Net Profit Before Tax (commonly referred to as NPBT), Net Ordinary Profit After Tax (commonly referred to as NOPAT). If a company shows continuing losses, this is a positive sign of financial distress and forensic accountant will seek to undertake further financial analysis (including analysis of sales, gross profits and expenses) to understand the causes for poor profitability and evaluate whether the causes are a likely to be fatal to the business.

Poor cash flow indicators

The following are positive indicators of financial distress faced by business and red flags that the company may be insolvent:

- Taxes not being paid on time, particularly payments of Pay As You Go – Withholding (PAYG-W), Pay As You Go – Instalments (PAYG-I) and Goods and Services Tax (GST) as shown in the Running Account Balances with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

- Employee superannuation not being paid on time. There may be Superannuation Guarantee Charge (SGC) applied by the ATO.

- Poor relationship with banks and other debt providers – this will include overdraft limits being reached, difficulty or refusal to applications for increase to overdraft limits, default interest charges, shopping around for debt finance with multiple banks and debt providers with any pre-approvals subject to onerous conditions, etc.

- No access to alternative finance, despite attempts being made.

- Suppliers remove credit terms and placing the business on COD terms.

- Long creditor days.

- Special arrangements with selected creditors;

- Inability to raise further equity capital, despite attempts being made.

- Issuing posted dated cheques.

- Dishonoured cheques.

- Judgments/warrants/solicitors letters issued in relation to services provided and/or outstanding debts.

- Rounded payments to suppliers not reconcilable to actual invoices.

Poor financial records

Section 286 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) provides an obligation on a company to keep financial records consisting of written records that:

- correctly record and explain its transactions and financial position and performance; and

- would enable true and fair financial statements to be prepared and audited.

Section 588E(4) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) provides a presumption of insolvency (in recovery proceedings) if it is proved that the company:

- has failed to retain financial records in relation to a period for the 7 years required by subsection 286(2).

- has failed to retain financial records in relation to a period for the 7 years required by subsection 286(2).

A common feature of a companies which are placed into liquidation are companies with poor financial records, typically being companies that have long delays with regards to preparation of management accounting reports and annual accounting reports for submission of income tax returns and business activity statements on time. One of the reasons why a company which continually lodges income tax returns and business activity statements late is because it is failing to keep financial adequate financial books and records which explains the financial performance and financial position of the company and the company is unable to obtain timely information in order to take corrective action.

A forensic accountant will therefore consider the sufficiency and quality of the financial documents it reviews to inform an opinion on the solvency of the company and financial viability of the business.

Conclusion

There is no one determinative factor which determines whether a business is financially viable and whether a company is insolvent. A forensic accountant will need to analyse and consider tests relevant to historical financial performance, historical financial positions, cash flow and financial records to form a view on the financial viability of a business and company’s solvency.

Read more about our expertise.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: