Strategic guide to concurrent evidence in Australia

Behind the 'Conclave' from an Expert's perspective

For litigators managing expert witnesses, the 'conclave' and 'hot-tubbing' can be a highly unpredictable phase of the litigation process. A well-managed expert witness in this process is a strategic asset that forces favourable settlements and wins bench decisions. A poorly prepared one becomes a material liability. Drawing from over two decades of experience, here is what every litigator and expert witness needs to know about concurrent evidence from an expert's perspective.

Understanding the battlefield: Primer on Concurrent Evidence

Concurrent evidence is a distinct feature of the Australian civil litigation system, which encapsulates:

- Conferencing between the expert witnesses instructed by adversarial parties, sometimes referred to as the 'experts' conclave' (although the terms conference and conclave can have subtle differences as explained below);

- Preparation of a written report by those expert witnesses, being the expected outcome of the experts' conference or conclave; and

- Tendering of oral evidence, by those same expert witnesses, during the same court session (colloquially referred to as 'hot-tubbing').

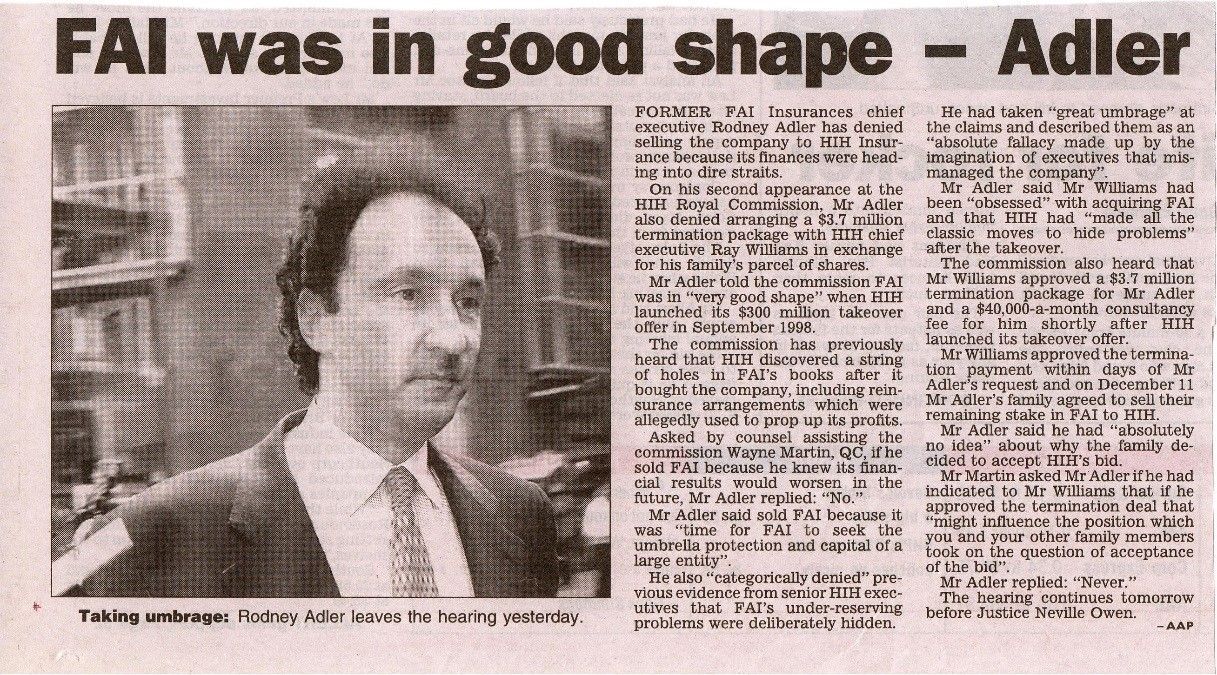

The reality of hot-tubbing

Hot-tubbing is a loaded term. More helpfully, the website of the Judicial Commission of NSW contains instructional videos in relation to the provision of concurrent evidence during a final hearing (i.e hot-tubbing), made in or around 2005 featuring a land resumption case in which the expert witnesses were involved, in what seems to be an open conversation between each other and the judge, after the barrister asked a question. My own experience of being in a ‘hot-tub’ has varied considerably across courts, ranging from being invited by ‘my counsel’ to provide the court with an opening statement about my evidence before being questioned by the judge and barristers organaised by topic area, to a very tightly controlled process by the barristers, akin to a more traditional adversarial process, in which each barrister take turns to question the expert witness instructed by the other side on a serious of topics, with little opportunity for the other expert to speak unless the judge intervenes to ask a question. The presiding judge will therefore influence the tendering of oral evidence from the witnesses appearing concurrently.

Case management involving concurrent evidence

Case management across the superior courts of Australia varies between courts and is often case-specific. While the application of concurrent evidence features in many litigated matters across Australia, it is not necessarily the default system across the superior courts of Australia.

The Honourable Justice Lee of the Federal Court of Australia has authored the Joint Expert Conclave Protocol for this. This protocol includes, amongst other things, two somewhat unique features relating to the management of the conference of expert witnesses, being

- use of a 'Facilitator', typically an independent barrister, who manages the experts during the conference to assist them in preparing a useful joint report for the Court; and

- supply to the expert witnesses about to conclave, a pre-agreed set of questions to answer in a jointly prepared report. Typically, for forensic accounting and valuation-related expert witness engagements, the expert witnesses are opining on matters concerning quantum, so it is less common for instructing solicitors on adversarial sides to consider and agree on a set of questions for the expert witnesses to answer. In this type of expert witness scenario, it is understood that the expert witnesses will be assisting the court by providing their respective reasoning on the quantum of loss or value. However, that is not to say there should be no communication between instructing solicitor and expert witness, before the commencement of the experts' conference/experts' conclave to address other potentially relevant questions for expert witnesses to answer that could assist the court.

Courts across Australia are harmonised, meaning there is a process of making different systems, rules, or practices consistent or compatible with each other in an effort to achieve uniformity across different legal jurisdictions. However, the process and language adopted are not uniform across all the superior courts of Australia. In Western Australia, the terms 'expert conference' and 'expert conclave' are set out in practice direction 4.5.2 Expert Evidence of the Consolidated Practice Directions updated by the Supreme Court of Western Australia in May 2024, are distinct to make explicit that the Registrar of the Court is involved in the latter, akin to Justice Lee's FCA Joint Experts Concalve Protocol featuring the use of a Facilitator.

Navigating the unfacilitated conference of expert witnesses

In preparing the primary report for court, containing one's opinion evidence, the key steps are:

- identify what you need and how to get it;

- analyse what you get, make further enquiries as appropriate; and

- proceed to write and finish your report, furnishing the opinion which you are qualified to provide with sufficient reasoning.

Sure, there can be challenges for the expert witness along the way within each of the above steps, but he or she can guide others and take control of how the report is prepared for the court with the assistance of lawyers. Assuming one has to appear in court to be cross-examined, one is thoroughly prepared to answer questions in discharging one's paramount duty to assist the court.

In contrast to preparing one's expert witness report and appearing in court to give oral testimony, the unfacilitated 'experts' conference' culminating in the joint experts' report can be a unique hurdle to jump over!

When it comes to the preparation of a joint expert report, seasoned litigators and expert witnesses are acutely aware that the courts' code of conduct for expert witnesses requires that the joint experts' report set out matters of agreement and disagreement, including the reasons for disagreement. Unfortunately, the unfacilitated experts' conference can be relatively more painful than it needs to be if:

- you (as an expert witness) have not previously done this exercise of conferencing with another expert witness, sans direction from the instructing solicitors, and not had prepared a joint experts' report;

- the other expert witness is not a professional (full-time) expert witness; and/or

- the other expert witness is less concerned about discharging the paramount duty to assist the court, and more concerned with maintaining a position in fear of what the lawyers or clients might think if there is a retreat from a previously expressed position.

The above manifests in different ways, and the other expert witness(es) instructed by the opposing lawyer can make the unfacilitated experts' conference process more stressful than it ought to be.

Over the past decade, I have been called to enter into many unfacilitated conferences with other expert witnesses on different occasions throughout the course of any year. The following is a litigator's checklist to help ensure your expert witness is ready for the conference with the adversarial party's expert witness, assuming the conference will not be facilitated by an independent person.

Litigator's checklist before the unfacilitated conference of experts

- Mandate early engagement. Don't wait for a court order. Proactively talk with your expert witness and get the expert's views on when this process should be started, as often there may be meritorious reasons to start sooner rather than later. This also obviously requires engagement with the adversarial parties' legal representative. Early engagement narrows issues sooner, reducing costs and creating powerful settlement leverage.

- Secure the experts' bandwidth. The expert witnesses should give themselves the capacity to fully engage in the process of conducting the conference, without distraction. This would include making sure your expert witness has delegated unrelated work to others, to have the capacity to do their best work during the conference.

- Coach the desired outcome. Assume the matter could proceed to a final hearing, and if this happens, the joint experts' report needs to be a useful document to assist the court and to present your expert witness' opinion as the opinion which should be preferred by the judge. In relation to assisting your expert witness in preparing a useful document, share your preference on the style of the joint report that would assist the court, especially if there is agreement with the adversarial parties' legal representative as to style. There are two polar distinct template styles which are common being: a) a 'Scott Schedule' where a table is prepared with the issue of the left of the table and each expert's response to the right of the identified issue, or b) sequential paragraph numbering where one expert drafts what he or she wishes to write for a particular topic, followed by the other expert writing what he or she wishes to write on that same topic. Some expert witnesses may be inflexible on style, in the absence of any prior direction, which may result in suboptimal joint expert reports. A Scott's Schedule style of joint report typically works best when there is a pre-agreed set of questions to be answered (which would and should involve the expert witness' input in formulating the questions prior to the conference commencing).

- Eradicate advocacy from your expert witness. An expert who appears as a partisan advocate destroys their credibility—and by extension, yours—in the eyes of the judge. Remind your expert that emotional language is a sign of a weak argument. In interacting with your expert witness, get insight on whether he/she might allow emotions to creep in during an expert witness conference, including saying and writing things that make the expert witness look unprofessional. The other expert is unlikely going to point out drafting by your expert witness makes him or her look like an advocate. Suggest to your expert witness to find the right words when drafting a joint experts' report to open the door for the other expert to gracefully retreat from what at first seems like an issue of disagreement and ultimately an unpreferred opinion.

- Insist on transparent communication on timing. While the expert witnesses should be free to agree to disagree on matters of opinion, and not seek instructions from instructing solicitors, during the experts' conference. The lack of regular communications between the expert witness and the instructing solicitor during a conference of expert witnesses does not mean there should be complete radio silence between lawyers and witnesses. Insist that your expert witness should agree with the other expert witness on a proposed realistic due date (if a due date has not been set by the court) and communicate this date to the instructing parties, and if it subsequently becomes obvious to the expert witnesses that the due date will not be achieved, communicate this to the instructing parties with a revised date for completion. Remind your expert witness that the parties may want to settle the matter before a judge decides the outcome, and submitting a long and detailed joint report that does not give both parties sufficient time to consider its contents before a final hearing has started makes it more difficult for the parties involved in litigation to consider settling the matter.

- Have an escalation plan involving uncooperative experts. If the other expert is obstructive, your expert witness' documented efforts to collaborate with the other expert witness may become powerful ammunition to petition the court for a facilitated conclave, reframing the problem as a procedural necessity to assist the court. To avoid reaching this point, always encourage your expert witness to seek to narrow the issues in dispute with the other expert by suggesting the court is likely to view both expert witnesses favourably if a joint report can identify as many areas of agreement as possible, particularly where there are significant issues of disagreement. Where the expert witnesses are opining on matters of quantum, this may involve explicitly alerting your expert witness to be prepared to accept the other side's assumptions, even though they are rigorously disputed by your side, in order for your expert witness to appear impartial and be of assistance to the court.

- Encourage your expert to be pithy. Brevity in a joint experts' report should not be achieved at the sacrifice of providing sufficient reasoning for an opinion by an expert. For opinions based on forensic accounting and/or valuation expertise, the matter of disagreement boils down to matters of quantum. If this is the case, remind your expert to always consider what is drafted in a joint experts' report in the context of its relevance to quantum in dispute. As you would know, the judge is not required to make a finding on which expert witness is technically correct on an esoteric point, so encourage your expert witness to focus on the reasoning for disagreement on an issue which is materially significant to the court in terms of deciding on matters of quantum.

The process of concurrent evidence, when navigated skillfully by litigators and its retained expert witness(es), can transform procedure into a decisive advantage. Concurrent evidence provides a clear, side-by-side comparison for the judge and often reveals the core strengths and weaknesses of each party's position. A successful conference of expert witnesses isn't about winning a debate with the other expert; it's about winning the trust of the judge, assuming the matter proceeds to a final judgment. It transforms your expert from a mere witness into a decisive strategic asset.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: