What is True Value?

The High Court of Australia provides guidance

Before addressing what is meant by ‘true value', it is helpful to address bases of value, sometimes called standards of value, which describe the fundamental premises on which the reported values are based on, and also consider the meaning of ‘market value’.

What is meant by 'standard of value'?

There are many different standards of value, including but not limited to ‘book value’, ‘fair value’, ‘market value’, ‘investment value’. In a valuation report, the standard of value adopted should be clearly identified. For example, the book value of an investment asset in a company’s annual report, may not be the same as the market value of that investment, and there could be a considerable difference in dollar amount between its book value and market value. For this reason, the standard of value should not only be identified in a valuation report, the adopted standard of value should also be clearly defined and explained given a different value amount can be justifiably stated depending on that standard of value adopted.

What is 'market value'?

The most common standard of value adopted when preparing a valuation report is ‘market value’.

Market value (sometimes referred to as ‘fair market value’, particularly in the context of valuing real estate) is a widely used concept inside and outside of Australian courts. From a legal perspective, the concept of market value is a well-established one, often referred to by Australian courts as the Spencer test, with the following cited:

“In my judgment the test of value of land is to be determined, not by inquiring what price a man desiring to sell could actually have obtained for it on a given day, i.e., whether there was in fact on that day a willing buyer, but by inquiring "What would a man desiring to buy the land have had to pay for it on that day to a vendor willing to sell it for a fair price but not desirous to sell?"[1]

Australian taxation law uses the term ‘market value’ throughout multiple sections within different statues, but these various statutes do not actually provide a definition of the term ‘market value’. Fortunately, valuation professionals, and others, can refer to a uniform definition for ‘market value’ and associated commentary within International Valuation Standards (IVS) published by the International Valuation Standards Council[2].

IVS provides the following definition for ‘market value’ being:

“The estimated amount for which an asset or liability should exchange on the valuation date between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm’s length transaction, after proper marketing and where the parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently and without compulsion.” [3]

IVS amplify on the above definition of market value by setting out the following significant matters concerning the meaning of ‘market value’[4]:

a) The expression of market value is at a “valuation date”, reflecting an expression of value at a particular point in time.

b) Market value reflects a hypothetical or actual transaction between a “willing buyer” and a “willing seller”. A willing buyer and a willing seller are neither over-eager nor determined to buy/sell at any price.

c) An “arm’s length transaction” is presumed to be between unrelated parties, each acting independently. Observations of transactions involving related parties do meet this criterion.

d) “After proper marketing” means that the asset has been exposed to the market in the most appropriate manner to affect its disposal at the best price reasonably obtainable. A ‘fire-sale’ of an asset to quickly realise cash because the seller is in financial distress likely reflects a condition which would not reflect a sale under market value conditions.

e) Where the “parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently” presumes that both the willing buyer and the willing seller are reasonably informed about the nature and characteristics of the asset, its actual and potential uses, and the state of the market as of the valuation date.

Importantly, in forming a conclusion on the ‘market value’ of an asset at a historical valuation date, the use of hindsight is considered not appropriate in forming an assessment of the market value of the asset because the information on which the valuation is based should, in general terms, have been in existence at or before the valuation date. More specifically, only those things which are ‘known’ or ‘knowable’ at the valuation date should be considered. The use of the term ‘knowable’ includes information that could be obtained with a reasonable degree of due diligence.

Amongst valuation and forensic accounting professionals, the definition and principles supporting the meaning of market value are universally adopted and therefore not contentious, notwithstanding that the different professionals may disagree on the amount representing market value at a point in time.

What is 'true value'?

True value is not a standard of value which a valuation professional typically adopt when preparing a valuation report to support a transaction or for financial reporting purposes.

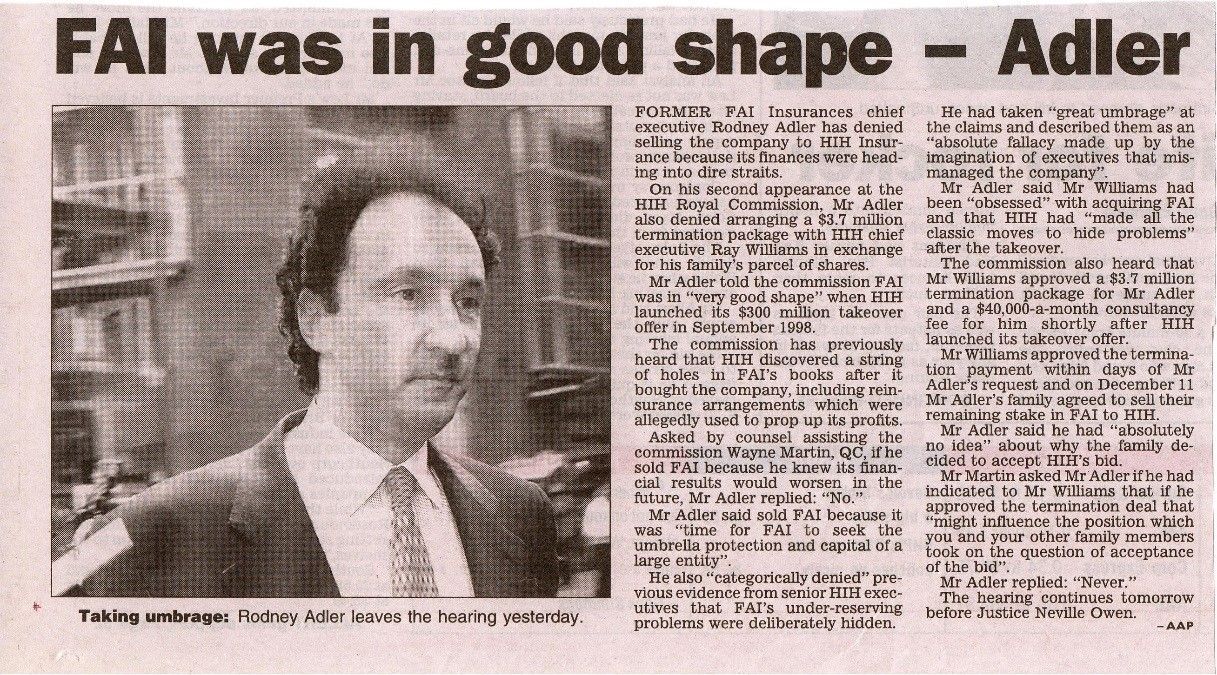

The concept of true value is a legal one, quite old[5] and typically used in the context of someone fraudulently enticing an investor to purchase an asset and perhaps more generally in misleading and deceptive conduct under different statute where the legal remedy sought is damages. True value is also commonly used in the context of estimating damages in shareholder class action litigation[6], which also falls within the paradigm of misleading and deceptive conduct legal matters.

In this context, Australian courts have referred to true value as ‘real value’[7], ‘fair or real value’ [8] or ‘intrinsic” value’[9] or ‘actual value’[10] or what an asset is ‘really worth’[11] or ‘truly worth’[12]. Australian courts have also referred to true value as ‘fair value’[13].

Australian courts have also consistently held, in the context of misleading and deceptive conduct litigation matters:

a) that the proper measure of damages is the difference between the real value of the thing acquired as at the date of acquisition and the price paid for it[14]; and

b) ‘true value’ can be different from ‘market value’ where market value is “delusive or fictitious” which may be the result of market manipulation or some other improper practice on the part of the vendor, or where the market operates under some material mistake[15].

Unlike the succinct definition of market value which can be found in IVS, there is no reference to ‘true value’ (or real value, or intrinsic value) in IVS. In the context of seeking to quantify damages in misleading and deceptive conduct litigation, one must appreciate what Australian courts have said about true value and its distinction from market value.

The High Court of Australia has stated[16]:

“although the value is assessed as at the date of the acquisition, subsequent events may be looked at insofar as they illuminate the value of the thing as at that date. A distinction is drawn, however, between subsequent events that arise from the nature or use of the thing itself and subsequent events that affect the value of the thing but arise from sources supervening upon or extraneous to the fraudulent inducement. Events falling into the former category are admissible to prove the value of the thing, those falling into the latter category are inadmissible for that purpose. Thus, the takings of a business subsequent to purchase are generally admissible, not only to prove that a representation concerning the takings was false but also to prove the true value of the business as at the date of purchase. Even when some difference exists between the conditions under which the business was conducted before and after purchase, evidence of subsequent takings may be admissible, "subject to due allowance being made for any differences in relevant conditions". But if it is established that the decline in takings has been caused by business ineptitude or unexpected competition, evidence of subsequent takings is not admissible to prove the value of the business as at that date, events such as ineptitude and unexpected competition being regarded as supervening events. In some cases of deceit, it may also be proper to compensate the defrauded party not only for the difference between the value of the thing acquired and the price paid for it but also for losses induced by the fraud and directly incurred in conducting the business.” [author’s emphasis is underlined]

In a nutshell, ‘true value’ is all about the courts applying the benefit of hindsight to form a view on value at a historical point in time[17]. In contrast, the accepted principles for a definition of market value include that it is not appropriate to apply the benefit of hindsight to form a view on market value at a historical point in time.

The challenge for independent expert witnesses assisting the court on matters concerning true value is making the distinction between subsequent events which are the cause(s) of the departure between price paid and true value which is considered intrinsic to the asset at the time when it was acquired, from those other cause(s) of departure between price paid and true value which is considered to be extrinsic, accidental, independent, or supervening[18].

In some matters, it may be appropriate for the independent expert witness to opine on a ‘true value’ of an ownership interest in entity conducting a business at a historical point in time. For example, in the IOOF class action litigation decision[19], the Federal Court of Australia was accepting of the lead plaintiff’s expert witness use of an ‘event study’ as a tool to calculate the ‘inflation ribbon’ representing the difference between the market price of the IOOF security and its ‘true value’ at a historical point in time, notwithstanding that no damages was awarded due to the inability of the lead plaintiff to prove its case on liability.

However, it may not always be straightforward or appropriate for an expert witness to decide what subsequent events are intrinsic or extrinsic to asset acquired in order to quantify true value at the date of acquisition of the asset. Given this, lawyers instructing expert witnesses to opine on true value in misleading and deceptive conduct litigation, ought to provide their expert witness with appropriate guidance (including well worded instruction letters, ideally with instructed assumptions supported by evidence) so the expert witness report assists the court to quantify damages.

Endnotes

[1]

Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia (1907) 5 CLR 418, per 432, Griffiths CJ.

[2] The International Valuation Standards Council is an independent, not-for-profit organisation committed to advancing quality in the valuation profession, with the primary objective of building confidence and public trust in valuation by producing standards and securing their universal adoption and implementation for the valuation of assets across the world.

[3] See IVS 104 – Basis of Value, paragraph 30.1.

[4] Paraphrased from IVS104 – Bases of Value.

[5] Peek v Derry [1887] 37 Ch D 541 at 591 per Cotton LJ, 594 per Sir James Hannen, 594 per Lopes LJ.

[6] McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v Insignia Financial Ltd [2023] FCA 1628 at 11, 102, 104,

[7] Twycross v Grant (1877) 2 CPD 469 at 545 per Cockburn CJ; Cackett v Keswick [1902] 2 Ch 456 at 468 per Farwell J; Potts v Miller [1940] HCA 43; [1940] 64 CLR 282 at 289 per Starke J; Toteff v Antonas [1952] HCA 16; [1952] 87 CLR 647 at 650 per Dixon J; Kizbeau Pty Ltd v W G & B Pty Ltd [1995] HCA 4; (1995) 184 CLR 281 at 291 per Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Gaudron and McHugh JJ

[8] Potts v Miller [1940] HCA 43; (1940) 64 CLR 282 at 299 per Dixon J.

[9] Potts v Miller [1940] HCA 43; (1940) 64 CLR 282 at 300 per Dixon J.

[10] Cackett v Keswick [1902] 2 Ch 456 at 468 per Farwell J.

[11] Stevens v Hoare (1904) 20 TLR 407 at 409 per Joyce J.

[12] Gould v Vaggelas [1985] HCA 85; (1985) 157 CLR 215 at 255 per Brennan J.

[13] Broome v Speak [1903] 1 Ch 586 at 605 per Buckley J; Ted Brown Quarries Pty Ltd v General Quarries (Gilston) Pty Ltd (1977) 16 ALR 23 at 31 per Gibbs J. It is important to note that ‘fair value’ has a very different legal meaning in the context of other types of litigation (e.g. corporate oppression matters) and for financial reporting purposes.

[14] Kizbeau Pty Ltd v W G & B Pty Ltd & McLean [1995] HCA 4 at 16 per Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Gaudron and McHugh JJ citing Holmes v Jones [1907] HCA 35; (1907) 4 CLR 1692 at 1702-1703; Toteff v Antonas [1952] HCA 16; (1952) 87 CLR 647 at 650-651; Gould v Vaggelas [1985] HCA 85; (1985) 157 CLR 215 at 220, 255, 265.

[15] Cargill Australia Ltd v Viterra Malt Pty Ltd (No 28) [2022] VSC 13 at 3918 per Elliot J.

[16] Kizbeau Pty Ltd v W G & B Pty Ltd & McLean [1995] HCA 4 at 16 per Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Gaudron and McHugh JJ.

[17] See also HTW Valuers (Central Qld) Pty Ltd v Astonland Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 54.

[18] HTW Valuers (Central Qld) Pty Ltd v Astonland Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 54 at [40] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Heydon JJ, citing Potts v Miller [1940] HCA 43.

[19] McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v Insignia Financial Ltd [2023] FCA 1628 at [291] to [326].

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: