Assessment date in damages & compensation

What is ‘damages’ reflecting a loss of profits? A simplified view

Before addressing the concept of an ‘assessment date’ as it relates to the issue of damages and compensation, it is useful to remind and emphasise that the principle behind a remedy of ‘damages’ is to restore the claimant to the position but for the claimed wrong, i.e. the cause of action.

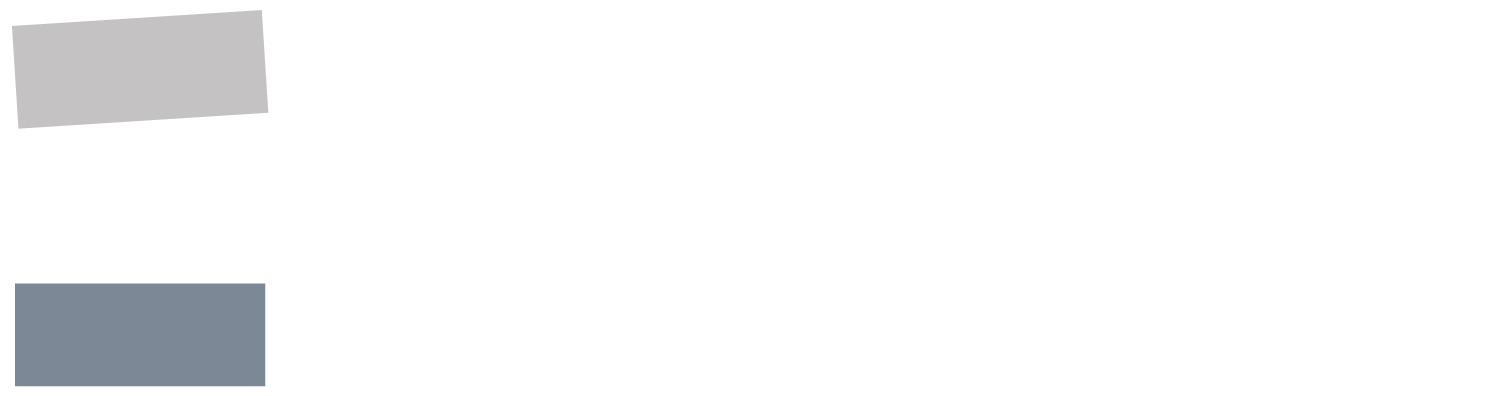

This principle of damages can be simplified and is shown diagrammatically in Figure 1 below, where the X-axis represents time and the Y-axis represents a level of, say, annual profit up to that point in time. Figure 1 shows the financial performance of a hypothetical business with a consistent level of historical profits (shown by way of the solid yellow line) up to a point in time when an event happens that gives rise to a cause of action.

A primary objective of the expert when quantifying damages is to determine what the profits of the business would have been, but for the cause of action event, being the dotted arrow line in Figure 1 above (and often dubbed a ‘but for scenario’). The expert will then deduct the actual profit as a result of the same event, being the solid arrow line in Figure 1 above (and often dubbed an ‘actual scenario’). The difference between the estimated profits in the but for scenario and actual scenario, represents, theoretically, the loss of profits caused by the event. The illustration in Figure 1 above uses straight lines and a highly simplified abstraction of reality for many businesses (particularly businesses emerging from COVID-19-related lockdowns over the course of 2020 to 2022).

What is meant by an assessment date in the context of damages?

Akin to the notion that an expert’s opinion on the value of asset is an opinion that reflects the value at a particular point in time, the assessment date in the context of damages represents the point in time that all of the losses, typically which may have accrued and continue to accrue over a period of time, are converted to a single number representing a ‘once-and-for-all’ lump sum amount as part of damages.

How is professional judgement relevant to an assessment date?

Quantifying damages requires the expert to consider different approaches, methods and procedures. This work includes applying mathematical calculations using various acceptable financial techniques and applying appropriate professional judgements about the relevant financial data to quantify one or more heads of loss.

One of the many professional judgements relevant to quantifying damages is selecting the appropriate assessment date, i.e the point in time to tally up all the heads of losses claimed.

In pure valuation engagements, the appropriate valuation date (being a current date and/or past date), is usually a function of the purpose of the valuation. Therefore, it is more obvious to know what the correct valuation date should be. However, in the context of quantifying damages and compensation, particularly involving claims for loss of profits, it can be less straightforward to determine the appropriate assessment date.

Theoretically, there are two (2) alternative points of time that could be adopted as an assessment date by an expert instructed to quantify damages or compensation which includes a claim for loss of profits:

- the date when the expert has tallied up the losses and presented an amount as damages, which is typically close to or the date of an expert’s report date. Adopting such a date requires what could be described as an ‘ex-post’ approach to assessing the quantum of damages; or

- the date of the cause of action, which is a historical date (and could be over a decade ago in some cases). Adopting such a date requires what could be described as an ‘ex-ante’ approach to assessing the quantum of damages.

Notwithstanding that Australian courts and tribunals are required to assess damages at the date of judgment in some particular matters[3], adopting a future proxy judgment date should not be used by experts for the damages assessment date. This approach would require adopting a hypothetical judgment date, which would be an unknown date in the future that assumes the court will award damages.

As there is no uniform rule as to the correct point in time when Australian courts award damages in all tort and breach of contract[4] (and therefore how the expert should assess damages), this paper addresses the relevant considerations for adopting an ex-ante and ex-post approach to assessing the quantum of damages and compensation.

What is an ex-post approach when assessing damages?

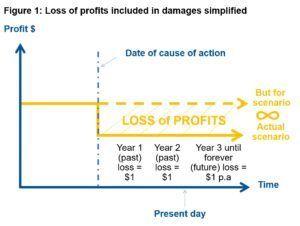

As shown in Figure 2 below, an ex-post approach requires standing at a point in time as close as possible to the current date and looking backwards from that date to calculate a ‘past loss’ and looking forward from that same date to calculate a ‘future loss’.

The use of an ex-post approach, in the case where business losses continue to accrue, will typically expressly distinguish the period of past losses separately from the future losses calculated. Figure 2 above reflects, standing as at present day, the pure mathematical outcome of adopting an ex-post approach is that the sum of all losses of profit in year 1 and year 2 are tallied to derive a past loss amount of $2. Future loss of profits (which are typically converted to a present value amount) will be added to the claim for past loss of profits and the sum of the past losses and future loss will be claimed as damages.

The use of an ex-post approach to assessing damages is widely accepted in personal injury negligence matters where heads of loss include things like past economic loss, future economic loss, past superannuation loss and future superannuation loss, amongst other heads of claim for damages.

In some other types of litigation matters, often involving tort, it may be appropriate to consider an ex-post approach, for example, in cases where there are multiple causes of action that extend over a long period of time (and maybe continuing). The use of an ex-post approach should be justified by the expert, for example:

- in cases where there is a repeated infringement of intellectual property rights, it may be possible to identify the specific quantities of infringing sales of products sold to date to calculate a loss using an ex-post approach assessment date; or

- in some compulsory acquisition of land matters, it may be appropriate to identify and quantify a loss of profit suffered by a business after the actual date of compulsory acquisition of land taking place prior to a physical relocation of the business – the quantification of such a loss would require the use of an ex-post approach assessment date.

What is an ex-ante approach when assessing damages?

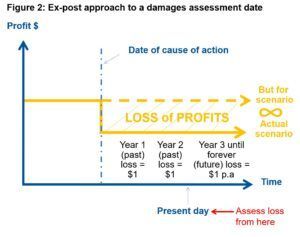

As shown in Figure 3 below, an ex-ante approach requires assessing the claimant’s total loss (as a single amount) as of the date of the wrong, i.e. cause of action. The assessment date would be a historical point in time, often many years from the present day.

The pure mathematical outcome of adopting an ex-ante approach is there will be a single amount assessed as the sum of all losses that arise from the date of the cause of action. The use of an ex-ante approach, in the case where business losses continue to accrue, does not necessarily require separate quantification of past losses and future losses – rather it is the present value amount of all losses suffered as a consequence of the cause of action. It is important to note from Figure 3, that the present value amount of the past losses will likely be something less than $2.

This use of an ex-ante approach, which assesses the loss as at the date of the cause of action is, generally speaking, a default position for assessing damages in a wide variety of litigated matters. Covell, K. Lupton & J. Forder’s text ‘Principles of Remedies’ states the following in support of an ex-ante approach for the relevant assessment date for damages in tort and breach of contract:

“Generally, damages [in tort] are assessed by reference to the date on which the cause of action arose, but the court has a discretion to fix its own date in order to provide fair compensation… In exercising this discretion the court will consider the fundamental principle of providing proper compensation for the loss.”

“The general principle is that damages [in breach of contact] are assessed at the date of the breach. The principle is not, however, applied rigidly…”

Why does getting the assessment date right really matter?

Generally speaking, the adoption of an ex-post approach, in preference over an ex-ante approach, will result in a higher calculated amount of loss of profits to be included as damages or compensation. Accordingly, uniformed claimants will gravitate to the use of an ex-post approach in the quantification of loss of profits because of this mathematical outcome. Experts wishing to maintain their independence as expert witnesses should not be drawn into adopting the assessment date which suits their client’s desired monetary outcome. The relevant and appropriate assessment typically features a related problem concerning the appropriate discount rate when calculating damages.

Most people are aware that $1 today does not equal $1 in, say, 5 years, due to the effects of inflation. Therefore, the use of the word ‘discounting’, as it relates to a claim for loss of profits forming part of damages, specifically factors in the time value of money. Most, if not all competent experts, would agree that it is necessary to discount future losses to reflect the time value of money principle.

However, experts may (often) disagree on the appropriate discount rate to apply to a stream of loss of profits, particularly those accruing in the future.

In negligence matters, such as a personal injury claim, falling under the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW), the discount rate in respect of future loss is prescribed at 5%[5]. However, a 5% discount rate involving a loss of profits suffered by a business involving a different cause of action (outside of personal injury) is usually not appropriate.

As the objective of discounting a stream of claimed loss of profits that arise at different dates over the future is to convert that stream of loss of business profits into a single lump sum that a court can award as damages or compensation, the opposing experts may consider an appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate that reflects the risks and timings associated with generating those profits.

The issues around determining the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate are within a technical area of specialisation involving valuation and finance theory and practice, which this paper does not address. In many litigation matters, opposing experts do not agree on the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate – one expert may adopt 10% and another expert may adopt 20%.

The present value of a stream of annual loss of profits, amounting to $100,000 (p.a.), over 5 years is:

a) approximately $379,000 using a 10% discount rate; and

b) approximately $298,000 using a 20% discount rate.

In this above example, a 10% increase in the risk-adjusted discount rate, opined on by an expert due to his or her subjective views on risks, has reduced the claim for loss of profits by $81,000 or approximately a 21% reduction in damages.

When experts disagree on an appropriate assessment date as to damages, the experts may also disagree on the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate. The conflated issues, almost always result in a material disagreement on the quantum of damages and calculations of interest on damages.

AVG Forensic has experts with a proven track record of giving persuasive expert opinion evidence which has been preferred by Australian courts over the other side’s experts.

Endnotes

[1] The principle of damages which is to restore the claimant to the position but for the wrong may also be reflected in the interpretation of statutory provisions of different Acts of parliament which may give rise to compensation entitlements (say for the compulsory acquisition of land).

[2] For example, if a valuation is required to support an impending sale or purchase of an asset, a current-date valuation is expected. If a valuation is required for tax-related litigation, the historical date of an actual transaction is typically the appropriate valuation date.

[3] Such as in personal injury and defamation matters.

[4] W. Covell, K. Lupton & J. Forder, ‘Principles of Remedies’, 6th edition.

[5] Other states of Australia have similar legislation which also prescribes the discount rate.

[6] The issues of assessment date for calculating loss of profits and the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate were addressed by AVG Forensic’s expert in the following matters where the Court preferred the expert evidence of AVG Forensic’s expert over the other side’s expert: Hudson v National Australia Bank [2022] FCA 1222 (14 October 2022), United Petroleum Pty Limited v Roads and Maritime Services [2018] NSWLEC 35 (23 March 2018) and The Trustee for Whitcurt Unit Trust v Transport for NSW [2021] NSWLEC 82 (30 July 2021).

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: