Valuation discounts – what are they, how to quantify them,& are they always relevant in disputes & litigation?

Valuation discounts - what are they, how to quantify them & are they always relevant in disputes & litigation?

This article addresses the highly contentious issue of ‘valuation discounts’ and their relevance in a valuation dispute, requiring expert evidence to opine on the ‘value’ of shares in a private company for potential or actual use in court proceedings. As detailed below, valuation discounts can be observed from empirical market data.

Consider an example of 3 equal shareholders in a very large private company operating a business. Let’s say that one shareholder wants to exit the investment in this private company (not related to any dispute). That shareholder would want the maximum possible amount, so should reasonably expect to receive a ‘market value’ consideration for those shares held in the private company.

The concept of market value is based on long-established common-law principles[1] involving a hypothetical or actual transaction between a ‘willing buyer’ and a ‘willing seller’, with both parties acting knowledgeably and neither being overanxious to transact. In this common, but hypothetical case example, let’s also assume:

- that it is possible to derive the value of the business operated by the company based on the price paid by a public company to recently acquire a comparable business; and

- there are no surplus assets or debt held by the subject private company (i.e. the value of the business and the value of the company are the same).

The question then becomes, is the market value of the exiting shareholder’s interest one-third of the value of the business?

The commercial reality is the ‘market’ would likely apply the following to the exiting shareholder's one-third interest in the private company:

- A discount for lack of control; and

- A discount for lack of marketability

What does a lack of control discount represent?

A lack of a controlling interest in a company, all other things being equal, is less attractive than a controlling ownership interest in the same company. This relative unattractiveness attracts a discount for a lack of control.

A lack of control discount represents the absence of additional rights that are afforded to controlling owners. The value of a controlling ownership interest depends on both the legal power and rights conferred by the holding, as well as the economic potential of exercising those rights. Examples of things a controlling owner may be able to do that a minority owner cannot, and are therefore considered valuable, may include:

- select directors, officers or employees;

- decide on levels of compensation for officers, directors and employees;

- decide with whom to do business and enter into binding contracts, including contracts with related parties;

- decide to pay dividends to shareholders and, if so, how much;

- register for listing on a stock exchange (assuming financial criteria for listing are met);

- make acquisitions or divest subsidiaries or divisions;

- buy, sell or hypothecate any or all company assets (assuming it is in the best interest of the company to do so);

- determine capital expenditures;

- change the capital structure;

- amend the company’s constitution;

- sell a controlling interest in the company with or without participation by minority shareholders;

- determine policy, including changing the direction of the business; and

- block any of the above[2].

How to calculate a lack of control discount?

It is possible to observe a premium paid for quoted prices of shares in a publicly listed company by an acquiring entity seeking to obtain control of that public company.

In Australia, studies have been conducted by different firms about control premiums paid by Australian companies operating in different industries. There are also similar studies conducted about companies listed on international stock exchanges. It is also possible for forensic accountants and valuation professionals to review Independent Expert Reports prepared for shareholders of public companies which are the subject of a merger or acquisition. These studies provide a range of different control premiums which can be observed, with different means and medians.

This article does not address in detail what these studies show. However, for illustrative purposes only, a forensic accountant and/or valuation professional might conclude that a control premium in the order of 20%, or significantly more, could apply based on one or more of those studies.

The fact that it is possible to observe a control premium allows for a calculation for a lack of control discount, which is the inverse of a control premium i.e. 1 minus (1 divided by (1 plus ‘control premium’)). For example, if one considered a 20% control premium would be applicable, an implied lack of control discount would be approximately 16.67%.

It is critically important to emphasise that valuation practice is based on sound professional judgements, which are subjective in nature. The application of a formulaic approach and observable data without any rationalisation of numerous and important professional judgments does not mean that a credible valuation opinion is produced.

What does a lack of marketability discount represent?

The marketability of an ownership interest in an asset (and in this article, considered in the context of a parcel of shares in a private company) refers to the owner’s (shareholder’s) ability to convert the asset (shares) into cash.

There are two dimensions to marketability; the price realised for the shares and the amount of time required to sell the share. These two dimensions are related as it may be possible to reduce the time taken to sell the share, by discounting the price. The more marketable a particular parcel of shares, the greater the ability to sell the parcel of shares at the desired price. In this sense, the lack of marketability is also referred to as illiquidity (and the lack of marketability discount can also be referred to as an illiquidity discount).

A parcel of shares in a public company listed on the Australian Securities Exchange can be easily and readily sold when there is typically a high volume of shares in that company bought and sold between parties daily. In contrast, it usually takes much longer to sell a parcel of shares in a private company and there may be additional costs to advertise and market the shares for sale.

How to calculate a lack of marketability discount?

Various studies of empirical data seek to identify a lack of marketability discount. These studies can be categorised into two types:

- Initial Public Offering (“IPO”) studies. IPO studies examine the prices of transactions in shares of private companies, compared to the eventual IPO price of the same companies to estimate the premium paid for tradable, marketable shares, and conversely the implied discount for the lack of marketability.

- Restricted stock studies. These studies compare the trading prices of a company’s publicly held stock sold on the open market with those of unregistered or restricted shares of the same company sold in private transactions. These publicly available restricted stock studies relate to non-Australian companies.

It is relevant to acknowledge that a lack of control in a private company will manifest into a lack of marketability attached to the minority ownership interest, as this ownership interest does not have control of the company (and business) and therefore the parcel of shares is less marketable. While valuation theory and practice recognise that a lack of control discount and a lack of marketability discount are separate discounts, it can be difficult to objectively allocate separate discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability. Care is required to avoid a situation where risks are double-counted in valuation.

The lack of marketability discount is, unavoidably, ultimately a matter of professional judgment, based on the analysis of the relevant facts for the subject company.

Does a discount for lack of control and/or lack of marketability always apply?

About the hypothetical example of 3 equal shareholders in a very large private company operating a business, where one shareholder wanted to exit the company, valuation professionals would likely agree that the ‘market’ would apply a discount for lack of control and lack of marketability to that shareholder’s interest. However, valuation professionals (and brokers) are likely to have different views on the quantum of such valuation discounts. In the context of disputes and litigation, the applicability of such valuation discounts is less straightforward.

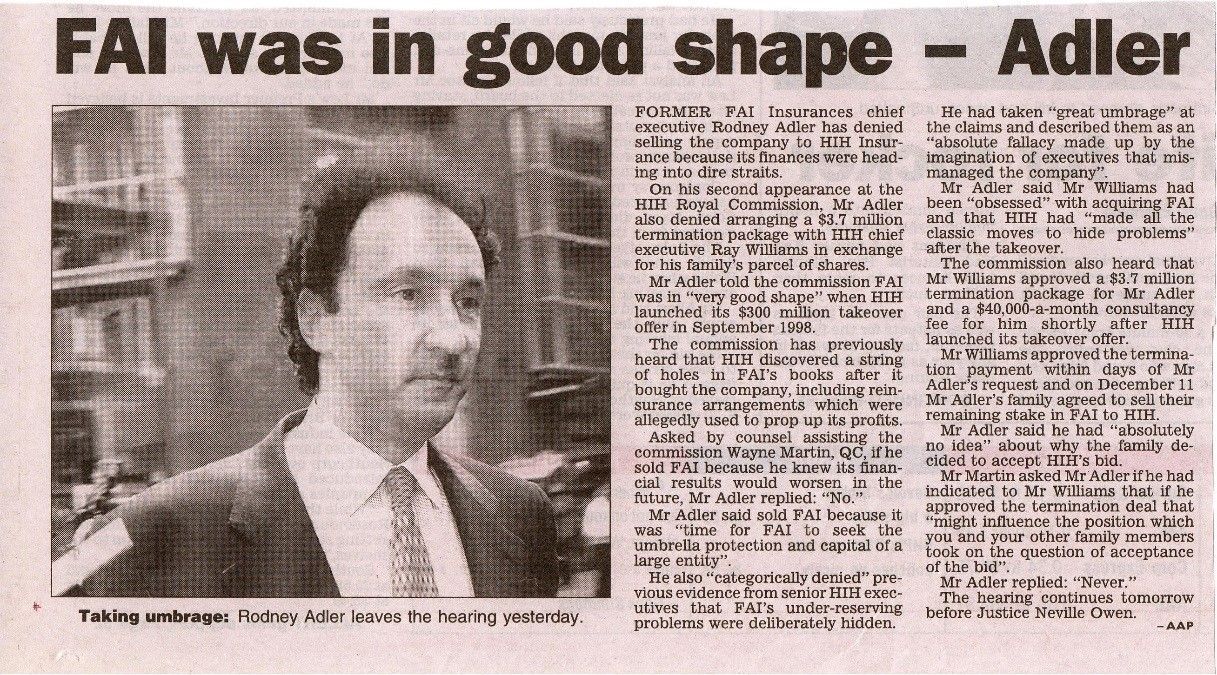

In tax disputes, the standard of value known as ‘market value’ is typically prescribed by statute, so its adoption ought not to be contentious. However, while it is generally accepted that market value would require consideration for a lack of control and lack of marketability, it does not follow that a minority ownership interest in a private company requires consideration and quantification of these valuation discounts. For example, in the case Commissioner of Taxation v Miley [2017] FCA 1396, where there were 3 equal shareholders, the Court determined, based on the relevant facts of that case involving an actual sale of the company’s shares to an arm’s length third party, by all shareholders, no discount for a lack of control should be applied to the one-third interest sold by Mr Miley.

In the context of the compulsory acquisition of shares, under section 667C of the Corporations Act 2001, the term ‘fair value’ is specifically used for establishing the value of the shares to be acquired. This section prescribes the steps in which this should be done that effectively and disregards any discount for a lack of control attached to the parcel of shares held[3].

In the context of shareholders who are employed by a company to operate a business and who can no longer work with each other, the resolution of the shareholders' dispute is often dependent on an agreement reached on the value of a particular shareholder’s interest in the company. Thus requiring one or more shareholders, to buy out the other shareholder, which implies the seller is agreeable to the price (i.e. there is agreement on market value).

However, in the absence of a shareholder agreement prescribing the standard of value that should be adopted, the issue of whether a discount for lack of control should apply can be vexed[4]. Even if such a discount should apply, what quantum should apply can be contentious and may prevent the shareholders from reaching an agreement over the value of the shares.

In cases involving claims for oppression under section 232 of the Corporations Act 2001, the courts have wide-ranging powers to remedy oppressive conduct which includes an order for the members’ shares to be acquired under section 233 of the Corporations Act 2001 and setting the price for those shares. Potential claims for oppression by a disgruntled shareholder and the potential remedy to have the court adopt a standard of value that is different from market value (such as ‘fair value’ as addressed earlier) can result in strong disagreement over the applicability of a discount for a lack of control attached to the parcel of shares (representing a minority ownership interest) in absence of a shareholders agreement.

In family law matters, Australian courts have referred to the concept of ‘value to owner’ which can be distinguished from the established principles of market value[5]. Without going into detail, the principles relating to 'value to owner' do not require any consideration of a 'hypothetical buyer' and therefore it may follow that it would be inappropriate to consider and quantify a discount for lack of marketability.

Conclusion

As forensic accountants and valuation professionals, we need to be mindful of the legal framework and purpose for which our valuation opinions are sought. While we can offer an opinion on matters of quantum of share value based on our expertise, the issue of whether a discount for lack of control and/or discount for lack of marketability should apply in a particular valuation engagement, involving a dispute, is ultimately a matter of law (i.e. ultimately for the Court to decide) and not necessarily a matter for the expert to opine on. We encourage instructing solicitors to provide forensic accounting and valuation experts, tasked with expressing an opinion on the quantum of share value, with case law that would be used in submissions to a court in a potential final trial hearing regarding the applicability of the above valuation discounts in the context of a particular valuation dispute.

Valuation discounts can be a source of disagreement in shareholder disputes where one or more shareholders wish to exit from the company. The highly subjective and contentious nature associated with quantifying a discount for lack of control and/or discount for lack of marketability provides specific context over why a shareholder agreement is worth having in place for companies (or unit trust) with more than one shareholder (or unitholder).

Endnotes

[1] In Australia, the principles can be traced to Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia (1907) 5 CLR 418.

[2] Pratt, S., 2009, Business Valuation Discounts and Premiums, Second Edition.

[3] Eight principles can be derived from the concept of ‘fair value’: Capricorn Diamonds Investments Pty Ltd v Catto & Ors [2002] VSC 105

[4] Where there is a shareholders’ agreement prescribing ‘fair value’ to be adopted, the valuation should ignore consideration of a discount for lack of control: Toll (FHL) Pty Ltd v PrixcarServices Pty Ltd & Ors [2007] VSCA 285, Candoora No 19 Pty Ltd v Freixenet Australasia Pty Ltd & Anor (No 2) [2008] VSC 478.

[5] Most recently in Gare & Farlow [2023] FedCFam C2F 109.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: