Loss Of Profits Claimed As Damages

Deeper dive into the ‘but for’ scenario

This article addresses the considerations of an expert, tasked with quantifying claims for loss of profit, as part of a claim for damages or compensation, as it relates to a ‘but for’ scenario. This article also addresses key documents that instructing plaintiff lawyers would likely need to help procure from their client to assist the expert to quantify damages.

The remedy of damages seeks to restore, in monetary terms, the claimant to the position it would have enjoyed but for a particular event giving rise to a cause of action in litigation. In relation to a claimant operating a business, the damages claimed will typically include a claim for loss of profits. A claim for loss of profit may also be imported into the paradigm of compulsory acquisition of land matters where a business is involved.

In factual circumstances where the business ceases to exist following the date of the cause of action, it may be appropriate to claim the value of the business, however, this article will not address a claim for damages representing the value of the business immediately before the date of the cause of action. While there are many similarities between a claim for loss of profits and a claim for business value forming part of damages, this article addresses the latter and not the former.

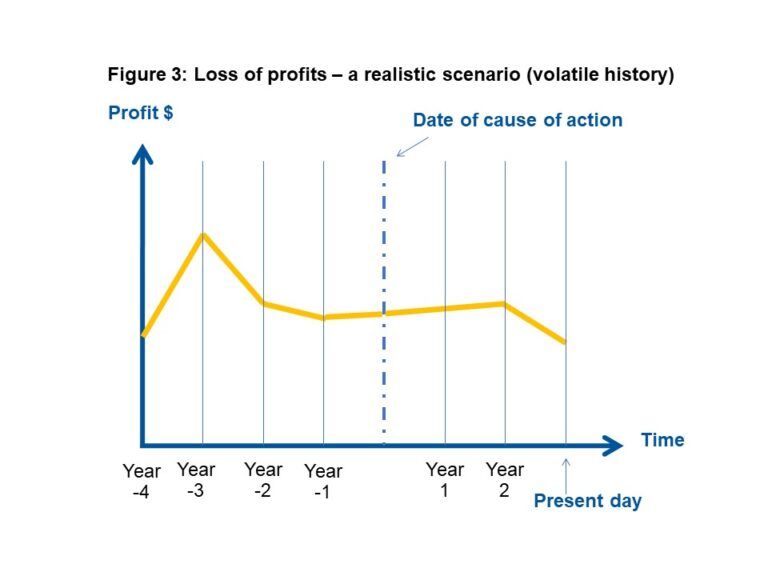

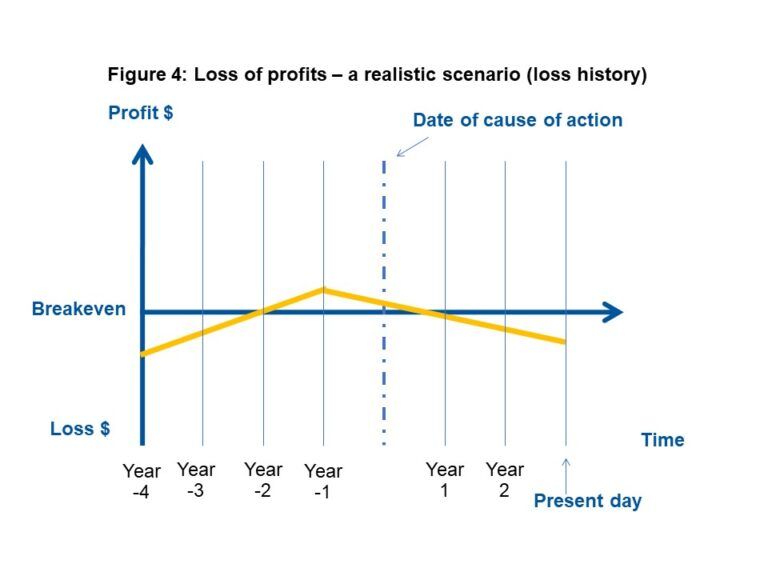

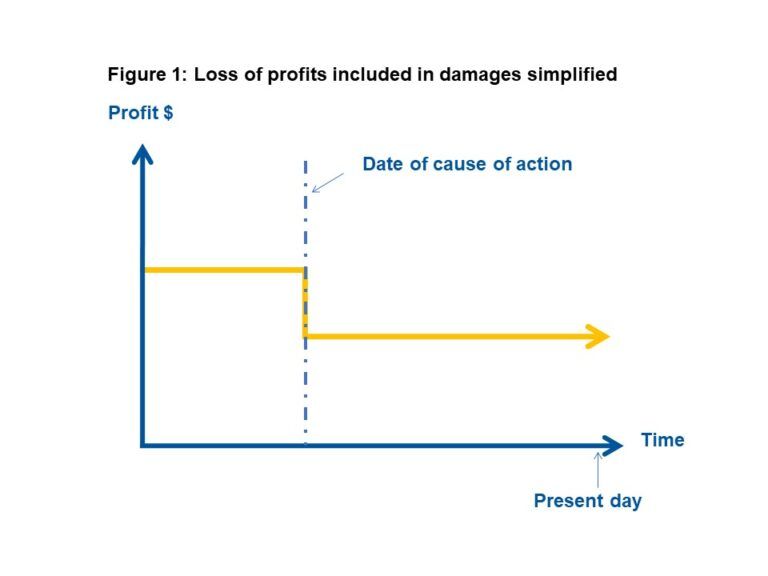

The key principles for quantifying damages can be illustrated diagrammatically and simplistically, using a line graph. As shown in Figure 1 below, the X-axis represents time and the Y-axis represents a level of annual profit at different points in time.

Figure 1 shows:

a) a business has a certain level of profits as shown by the yellow arrow and at a historical point of time, an event happens which gives rise to a cause of action (i.e. the right to commence litigation proceedings in a court); and

b) the profits of the business fall after the date of the cause of action relative to the profits of the business prior to the cause of action.

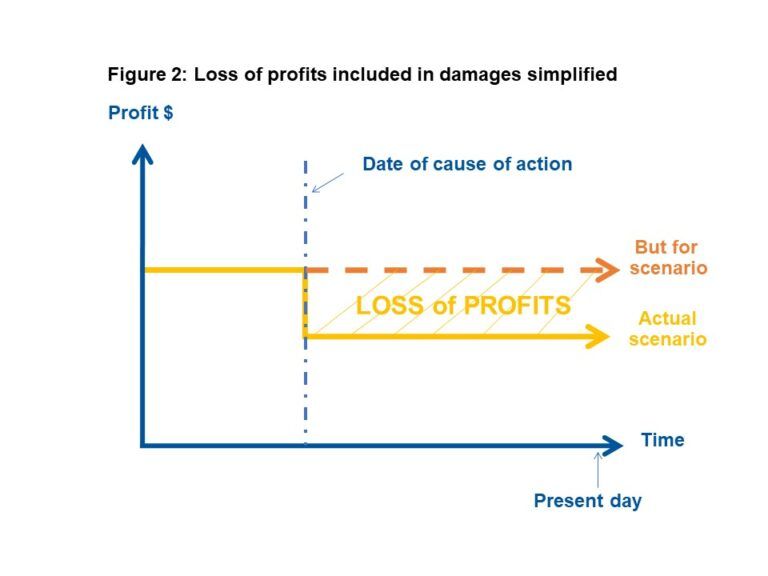

One of the primary objectives of the expert in calculating damages is to determine what the claimant’s profits would have been, but for the cause of action. Figure 2 below shows a dotted line reflecting the expert’s view on what the claimant’s profits would have been but for the cause of action.

In very basic terms, the difference in profits in the but for scenario (i.e. absent the cause of action) and actual scenario (i.e. as a consequence of the cause of action), as shown in Figure 2 above, represents the loss of profits that will be claimed as damages.

Common steps to calculate loss of profits in damages

The illustration in Figure 2 above is a simplistic illustration because it is not common to identify such an obvious pattern of profits before and after the date of the cause of action. Furthermore, the expert will also need to consider the following issues which are often matters which can be highly contested:

- Period of loss, i.e. when does the loss end? This is the convergence between the solid yellow line and dotted orange line shown in Figure 2 above. Standing at present day, it may be difficult to know with certainty as the point in time when the two lines will converge. In a breach of contract damages claim, it may be the point in time when the contract is assumed would have been completed, however, if the claim for loss is pleaded as a tort in the alternative, the loss may extend beyond the assumed contract completion date. The answer to this question will depend on the facts and may be the subject to expert evidence. Experts do need to be mindful, when claiming a long period of future loss, including a loss into perpetuity, that a plaintiff has a duty to mitigate its loss.

- What is the revenue in the but for scenario? There are three different methods that an expert might consider to opine on what the revenue would have been in a but for scenario, which is addressed in more detail below.

- Which costs are relevant? The subject of the claim for damages is a loss of profits. It is generally accepted that ‘net profit’ is the difference between revenue and costs. However, accountants can and do adopt many different measures for the net profit of business. In the context of a claim for damages, experts will often disagree on which costs are relevant. For example, rent for use of a business premises is typically a fixed dollar amount. In many scenarios, there may not need to be a deduction for rent expense in calculating damages, however, if the estimated revenue for a manufacturing business in a but for scenario is above the current production capacity of the business, then it would be necessary to make a deduction for rent for additional premises. The simple answer is that those costs which have a nexus with the revenue claimed to be lost are relevant and should be deducted from the revenue. This may include capital costs, finance costs and income tax (on taxable net profits calculated)

- Calculating present value of losses. This requires considering the appropriate assessment date and discount rate. The considerations regarding an assessment date in damages are addressed in this article. The considerations regarding a discount rate are addressed in this article.

An expert should consider the history of the business prior to the date of the cause of action and, in reality, observing a pattern that looks like that shown in Figure 1 above can be rare as the patterns observed in Figure 3, Figure 4 or Figure 5 below are far more common.

Documents to be procured and supplied to the expert as part of the initial briefing

Before plaintiff lawyers seek to brief an expert, plaintiff lawyers can assist by obtaining from their firm’s client and supplying the expert at the time of briefing with the following documents:

- Assuming the claimant is not a publicly listed entity, the claimant’s income tax returns for 5 years prior to the date of the cause of action and all years subsequent to the date of the cause of action;

- Assuming the claimant is not a publicly listed entity, the legal entity’s financial statements (comprising a balance sheet and profit and loss statement) for 5 years prior to the date of the cause of action and all years subsequent to the date of the cause of action; and

- Where the claimant operates more than one business division and/or geographical department and tracks the performance for each business division and/or geographical department, the internal management reports prepared by the claimant showing the income and expenses for the each business division and/or geographical department for 5 years prior to the date of the cause of action and all years subsequent to the date of the cause of action. If the claimant routinely prepares forecasts for its business as part of its management processes, the management reports should also show the actual performance compared to forecast performance.

The above documents are unlikely to be the population of relevant financial documents that the expert would need to consider to quantify a claim for loss of profits forming part of damages. However, it will be a very useful starting point to identify the performance of the business before and after the date of action and guide the expert on the further documents and information required to progress the claim for damages.

So what are the methods that an expert could apply to assess the revenues and net profits in a but for scenario?

Before-and-after method

As the name of the method suggests, a ‘before-and-after’ method assumes the business’ revenues which happened before the date of the cause of action would have continued after the date of the cause of action, absent the event giving rise to the cause of action.

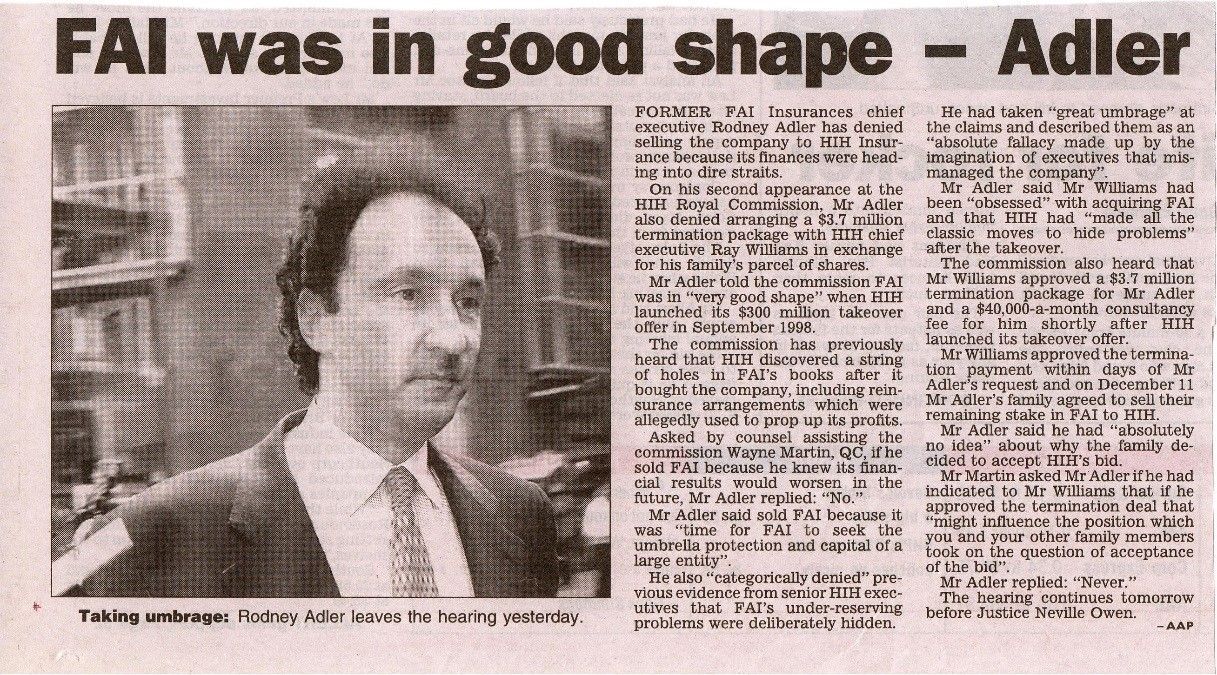

The before-and-after method requires obtaining historical financial data for the business for a sufficient and appropriate period of time before the date of the cause of action. The defendant’s expert may try to undermine the damages calculation by opining that the ‘after period’ is different to the ‘before period’. For example, the before period may be before the arrival and spread of COVID-19 and it would not be appropriate to assume that revenue generated by the business would continue in the period after the arrival and spread of COVID-19.

Comparable method

As the name of the method suggests, the comparable method relies on the performance of a comparable business or a group of comparable business (say the industry) and using that comparable as a benchmark to estimate the revenues the plaintiff would have earned but for the wrong perpetrated by the defendant.

This method is useful where there is an insufficient track record to apply the before-and-after method. Alternatively, this method can be used to support the findings of the before-and-after method.

A pitfall of the comparable method is that it is not based on the actual performance of the business in question but on a notional performance determined by comparison, which raises the question of whether the benchmark selected is in fact an appropriate comparable for the business. A proxy business may appear comparable on a qualitative basis (location, number of employees, sales offerings and other physical characteristics) but not necessarily comparable on a quantitative basis (i.e. its revenue is different due to other factors).

Acceptable proxy firm candidates should be similar in size, product line, markets and other relevant factors. Caution should be used before applying the comparable method, given the difficulty in identifying appropriate proxy firms.

Market method

As the name suggests, a market method to estimate revenue in a but for scenario is developed using assumptions arising from a study of the industry and of the plaintiff’s operating results in the context of the industry.

Typically, the market method requires an understanding of the revenues of the entire market in which the claimant is just player in and an understanding the claimant’s market share position in the periods prior to and after the cause of action. The market method is best suited to situations:

- where there is a high degree of concentration of key players in the market;

- the claimant was known to also be a key player in the market prior to the date of the cause of action; and

- the claimant is ‘sophisticated’ and ‘methodical’ in the sense that it has a clear business plan (outlining its strategy and tactics to achieve its vision) and prepares forecasts and tracks its progress against forecasts.

Whatever method or methods is/are employed by the expert to quantify the loss of profits, assumptions will need to be adopted. Some of those assumptions will be made by the expert forensic accountant or may derive from instructions to the expert from the claimant or other experts (say industry specialists, actuaries or economists). A seasoned forensic accounting expert witness should be able to identify to the instructing solicitor the evidential gaps that need to be filled before his or her expert evidence is finalised so that all assumptions underpinning the calculation of damages is well supported.

Endnotes

[1] This is a generalised statement as damages in breach of contract can include ‘reliance’ damages whereby the claimant seeks to recover the wasted costs incurred as a result of entering into the contract.

[2] Claims for loss of profit in compulsory acquisition of land matters must coincide within a statutory framework. Lawyers representing adverse parties may debate on whether the relevant statutory framework permits claims for loss of profit under a particular section of the statute relating to a compulsory acquisition of an interest in land.

[3] Standing in mid-2023 where there was the arrival and spread of COVID-19 in 2020 through to 2022 prior to the rollout of a COVID-19 vaccine, business operating across numerous industries were dramatically affected (negatively or positively) and therefore the results of the past 3 years may not be a sufficient period of normal trading conditions, hence why a 5 year period is suggested.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: