Navigating Legal Professional Privilege as a Forensic Accountant

How barristers educate and shape our thinking on legal professional privilege

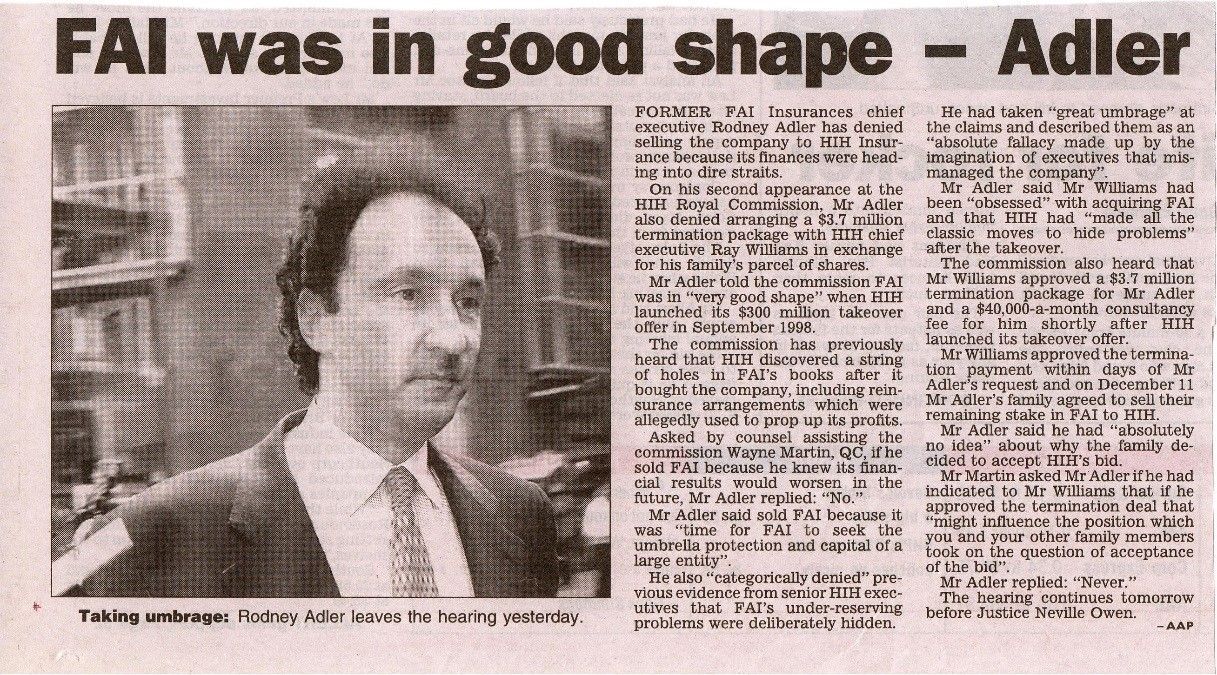

Anthony McInerney SC and Nicholas Bentley’s Australia Law Journal article (2025) - "Can You Really Claim Privilege Over Evidence That You Have Served? Reconciling Conflicting Appellate Authority and Modern Case Management Principles"

– brilliantly dissects the tension between traditional privilege doctrines and today’s push for efficient and transparent litigation. As a forensic accounting expert witness with 25+ years working in many different commercial disputes, I see this tension play out in the demands for workpapers, draft reports, and communications involving the expert witness.

Key take-away points from this article

Older jurisprudence, as cited in the article by Anthony McInerney SC and Nicholas Bentley, often maintained that privilege over working papers and draft reports survives until the expert’s finished report is tendered in court. This means that until that formal step occurs, these preparatory materials retain their confidentiality, which support claims for legal professional privilege. These authors contrast this with modern litigation principles, influenced by the push for "just, quick, and cheap" resolutions, identifying a shift that if a final report is disclosed (thereby laying all the cards on the table), then the associated materials which influenced that report should also be available to ensure that litigation proceeds on a level playing field.

The debate over whether working papers and draft reports should retain privilege when an expert report is served is more than academic. It affects:

• Litigation Strategy: A party’s decision on how to organise, review, and eventually serve an expert report can have long-term consequences, i.e. affect the outcome. If the preparatory materials are disclosed, then any inconsistencies or vulnerabilities in the expert’s analysis come under the spotlight.

• Expert Independence: Experts must be able to document their honest opinion free of undue influence from others. The communications with the expert and subjective statements in that process will be examined. Experts must also be aware that if their draft work is later inspected, it might be used to challenge their credibility or the validity of their conclusions.

• Judicial Efficiency: The modern approach seeks to avoid last-minute surprises at trial. By encouraging the disclosure of underlying materials before the hearing, parties can more efficiently resolve disputes or narrow down the contested issues.

Q&A on navigating legal professional privilege from a professional expert witness

I recently joined the authors of this article at a CPD event called 'Privilege vs. Practice: Navigating Conflicting Case Law in the Age of Case Management', to provide my perspective on this topic.

The questions & answers below delve into the operational realities expert witnesses face regarding document control and collaboration between lawyers and experts, often involving reliance on other witnesses. I preface all my answers that I am not meant to be an advocate for my client paying for my work and emphasise the importance for me to remain neutral to the outcome, e.g., my primary goal is to help the court. I align our firm's internal processes with this in mind. Maintaining rigor in arriving at my key conclusions is fundamentally important as too is operating on the pragmatic presumption that any part of my work could be required to be made available to 'other' side and to the court.

Question 1: What documents could be lawfully demanded from an expert witness in litigation?

In short, workpapers, draft reports, and communications are all potential items that may be demanded of an expert witness to be produced under a subpoena.

'Working papers' are essentially the internal notebooks of an expert witness and arguably the team supporting the expert witness, which include raw computations, unpolished analyses, brainstorming notes, and evidence gathering details.

'Draft reports' are the early versions of the final report, where the expert’s initial opinions and methodologies are laid out before refinement.

'Communications' are typically focused around the provision of instructions to me.

These categories of documents can capture the expert's thought process and the analytical journey toward a final opinion contained in the expert witness report.

Question 2: How do you handle requests for underlying documents (e.g., drafts, workpapers, etc) post-service of your final report? Do you see this as a challenge to your independence?

My firm presumes all materials from initial client enquiry stage to the date of the final trial hearing could be subpoenaed. This potential scrutiny ensures that I will be seeking to make all reasonable and desirable enquiries throughout this time period, undertake robust analysis to assist the court, and take precautions to withstand challenges to my credibility and persuasiveness as an independent expert witness.

The primary message to get across to the client(s) paying for my work (via the instructing solicitors) in the event of a subpoena being served is that time will be required to carefully review and consider every document on its own merits. There are usually documents in my possession that do not fall within the requests for certain categories of documents, so specific documents can reasonably be exempt from being produced. Unavoidably, in reviewing documents there is also consideration of potential questions that might seek to discredit me or questions to illicit answers that may be considered helpful to the opposing party without further qualification.

There is also typically a need to forewarn that the reasonable costs of compliance with the subpoena will be above the conduct money that has been provided.

Question 3: Given there is a tension between privilege and modern case management principles for transparency, how can forensic accounting expert witnesses assist in aligning their work with the 'cards on the table' approach while protecting legitimate confidentiality?

My primary focus is on delivering robust expert opinion evidence rather than assisting on procedural battles between adversarial parties. I leave it to the lawyers to argue over the merits of claiming legal professional privilege and using other arguments to object to the subpoena that could be served on me. With that said, the following are practical steps our firm takes take when preparing an expert's report to minimise disputes over privilege or waiver of underlying materials:

• Structured document management. Our firm maintains clear folder structures for all engagements, including segregation of client proposal/acceptance documents, tax invoices and supporting records, working papers, independent research, legal correspondence between parties, documents supplied to our firm, affidavit evidence, pleadings, draft report and final report.

It is important that any draft reports are clearly labelled as such, with any opinion contained therein being clearly stated as preliminary and could be subject to change in the final version. We are typically instructed to mark our communications with "subject to legal professional privilege", and we accordingly follow our instructor's advice to do so.

• Explicit reliance. If I make an assumption in my report drawn from reliance on a document, I cite that document clearly in my report so parties know that the document is part of my evidence.

• Proactive client warning. Our firm's engagement letter states that I need to be independent and be seen to be independent from the client and outcome sought by the client. In practice, this means the client paying for the my services should avoid direct communications with me, use their legal representative to supply documents to me including any assumed facts. This will help preserve any subsequent claims for legal professional privilege in relation to documents held by the client.

• Email minimisation. Solicitors can be busy and focused on other matters, so email can be used as a communication tool between expert and lawyers to provide updates on progress and/or identify problems in proceeding forward requiring decisions to be made. These communications can potentially be fertile ground for informal commentary that could be misconstrued. The less said in emails may be better, however, I always discuss preferred method(s) of communications with my instructing solicitors at the outset (as different firms and different lawyers have different preferences, especially parameters around email). The key principles to adopt are neutrality and to avoid speculative/or and adversarial language in any communications. Also, we limit sending our email communications to the law firm instructing us, and only to those who are on the legal client engagement team.

• Code of conduct for expert witnesses. Expert reports filed with the court that are dated on the same date of the instruction letter from the solicitor essentially invites the opposing party to seek production of all documents given to the expert. There can be valid reasons for why the instruction letter containing the question(s) to be answered by the expert has evolved over the course of the engagement. It is our recommendation that solicitors should not delay in the issue of a letter requesting the services of the expert to act as an expert witness and supplying the code of conduct for the expert witness, so this letter can be attached to the report to be served. This provides greater transparency to the adversarial parties and to the court over when the engagement with the expert witness commenced.

• Notes of meetings. Solicitors are better suited, over expert witnesses, to take contemporaneously prepared notes of meetings involving the expert witness and to prepare a clear summary of action points and any instructions given in respect of the meeting. The use of webconference, and potential for sharing of screens, is a matter for the lawyers to consider, noting that the expert witness is seeking to be transparent to the court in arriving at a concluded opinion.

Question 4: Where do you see the greatest risk for the potential for waiver of legal privilege?

Arguably, the greatest risk arises when instructed on pre-litigation matters. In pre-litigation matters, the legal team may not have all the facts, documents and key assumptions and there may be less formality around the process for supplying relevant documents and information from the client to allow me to carry out the forensic accounting work. Privilege preservation demands disciplined collaboration between lawyer, expert and client so I remind solicitors to manage our mutual client's litigation risks and for the client to take appropriate steps to preserve claims for legal professional privilege.

Matters where the plaintiff strongly believes the matter will resolve without a final hearing also presents risk.

Question 5: What can you practically do to help the client manage its risk for the potential for waiver of legal privilege?

Some clients may seek to bypass solicitors in the early dispute phase to "save costs." I would typically decline these engagements until there is legal representation overseeing the workflow. Solicitors are key to educate and remind their clients on steps required to preserve claims for legal professional privilege, and that the primary role of an expert witness is to assist the court (which overrides the duty to the client).

Occasionally, I take queries from potential clients informing me that their solicitor has said to them to make their own enquiries to find a forensic accounting expert. Typically, I am asked in this initial point of contact to provide an estimate of fees for an unclear scope of work, which requires asking more questions, and this process should ideally be led by the solicitors, and not the client involved in the dispute.

Conclusion

In an era where courts increasingly demand transparency, our protocols turn privilege management from a vulnerability into a strategic advantage in reaching a financial resolution in the dispute. Solicitors are encouraged to contact me to discuss privilege-proof engagement strategies involving client disputes as we welcome and encourage solicitor-filtered workflow

for our forensic accounting engagements.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE:

Attacking the messenger and the message! The practice of preparing valuation reports is well established in Australia. Despite the prevalence of numbers and calculations in a valuation report, valuation practitioners come from a variety of different backgrounds, which are not limited to those with an accounting and/or finance background. This has led to a haphazard and ad-hoc approach to setting quality standards across the body of valuation work in Australia. Attacking the messenger… From July 2008, members of Australia’s two largest accounting professions – the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia and CPA Australia – are required to adhere to APES 225: Valuation Services (“APES 225”). This sets out mandatory professional obligations on those providing a valuation service and has helped lift the quality of valuation reports. However, valuers who are not members of the accounting professions in Australia do not have to comply with APES 225. Up until 2014, there was no professional body in Australia that formally recognised practitioners who prepared valuation reports on businesses, part interest in businesses or legal entities, intangible assets and intellectual property rights. In late 2013, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia, merged with its counterpart in New Zealand (to form Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand) started a process of inviting its members who practiced in providing valuation services to become formally accredited as Business Valuation Specialists. This process required members to demonstrate a requisite number of years practical experience in addition to rigorous formal education. Those members which met the assessment criteria set by the Institute of Chartered Accountants are now are called ‘CA Business Valuation Specialist’. The concept of accredited specialists is not new to the legal profession. The benefits for lawyers and their clients, where lawyers are promoted as having formal accreditation in a particular area of law are apparent. It is hoped that the promotion of CA Business Valuation Specialists will also benefit lawyers and their clients as it will provide additional comfort that the quality of valuation reports prepared for dispute purposes will be fit for its purpose. Attacking the message… Unfortunately, there are still numerous business valuation reports prepared for dispute resolution purposes that are not fit for purpose. Here are the top 7 common problems we have encountered with business valuation reports: 1. Inappropriate ‘standard of value’ adopted in a valuation report. There are subtle but important legal differences between concepts such as ‘fair market value’, ‘fair value’ and ‘value to owner’ to name just a few different types of standard of value. This potentially means the value opinion could be materially different depending on the appropriate standard of value to be adopted. For example, in family law and compulsory acquisitions matters, ‘value to owner’ principles prevail. In shareholder/owner disputes, ‘fair value’ principles may be the relevant standard of value to adopt. Commonly, business valuations are prepared with ‘market value’ or ‘fair market value’ definitions – it is therefore not surprising that some business valuers struggle with the nuances and practical application of a different standards of value. There are numerous examples of courts rendering valuation reports as inappropriate purely on the basis that the wrong standard of value has been adopted. 2. Confusion between what is actually being valued in a business valuation report. The following concepts have very different meanings and therefore the value attached to each can be significant: ‘company’ or ‘entity’ value (where a legal entity other than a company is being valued; ‘business’ or ‘enterprise value’; ‘share’ or ‘equity value’ (where a part interest in a legal entity other than a company is being valued); and A parcel of shares or investor value. We have seen valuation reports which use all of the above terms inter-changeably which leads to confusion as to what is actually being valued. Lawyers instructing business valuers are not expected to know what precise term should be used in an instruction letter, however it is incumbent on the business valuer to clarify exactly what is being valued and provide a clear definition of this so as to not mislead readers of a valuation report. 3. Mismatch between the discount or capitalisation rate and earnings base. The following are different types of earnings bases: Earnings Before Interest Tax Depreciation and Amortisation (“EBITDA”); Earnings Before Interest Tax (“EBIT”); Net Profit Before Tax (“NPBT”); Net Profit After Tax (“NPAT”); Net Cash Flows before Interest; and Net Cash Flows after Interest. It is inappropriate, for example, to observe a published EBITDA multiple for a comparable company and apply an adjusted EBITDA multiple to the subject business’ EBIT, NPBT, NPAT or any other earnings base other than EBITDA. Similarly, it is also inappropriate to observe a published Price Earnings (“P/E”) multiple for a comparable company and apply an adjusted P/E multiple to the subject business’ EBIT, EBITDA, NPBT or any other earnings base other than NPAT. 4. The Future Maintainable Earnings figure is simply a 3 year average of the reported historic profits. Accounting profits can easily be manipulated by business owners simply because there is so much discretion available to the business owner. For example; Owner remuneration can be easily adjusted and the actual remuneration package can be disguised by unreported private fringe benefits. Business profits can be channelled indirectly to business owners via related party transactions. Travel and entertainment can be quasi-business related expenditure. The business premises can be owned by related parties with rent charged on a non-commercial basis. In addition to the above discretionary items that may require adjustment to the historic reported profits, the following are some additional considerations which may warrant it inappropriate to adopt a 3 year historic average of reported net profits: Expenditure or income relating to surplus assets (eg property) may be included in the profit & loss statements thus distorting what is the business’ normal earnings. The business requires significant future capital expenditure which is different to historical levels. The business suffers from a shortage of working capital either due to seasonality or more systematic liquidity issues. The products/services sold by the business and/or the industry it operates has passed through the maturity phase into a decline phase. The business operates in a volatile industry with fluctuating profitability. Despite what is apparent from so many valuation reports, simply averaging the last 3 years of reported profits is not a standard valuation procedure! What is appropriate is to attempt to ‘normalise’ the operating profits of the business and apply professional judgement to form a view that the level of normalised operating profits can be sustained into the future. 5. There is an insufficient understanding of the business to justify the discount or capitalisation rate. From a layman’s perspective, one of the biggest ‘mysteries’ of many valuation reports is how the valuer arrives at a discount or capitalisation rate. The valuer may be criticised, rightly or wrongly, that the report is devoid of any market data supporting the discount or capitalisation rate. The reality is that for many non-listed entities, particularly smaller businesses, is that there is very little, if any market data available on what the discount or capitalisation rate should be. Even if market data is available, there are often more reasons to not blindly rely on the data and apply a good dose of professional judgment regarding the discount or capitalisation rate based on the valuer’s understanding of the economy, industry and business specific risks. A high quality business valuation report will include sufficient detailed about the valuer’s understanding of how the business operates in isolation and within its environment. S.W.O.T analysis, Porter’s 5 Forces analysis, Life Cycle Analysis are all relevant analytical frameworks available to a business valuer to guide and rationalise the professional judgement applied regarding the discount or capitalisation rate. 6. Inappropriate valuation methodology and/or lack of cross check valuation methodologies. It is commonly stated that valuation is an art, not a science. I personally do not subscribe to this kind of commentary but I do admit that ‘value’ can be highly subjective – one person might perceive little value in a business whereas another person may perceive something very different. The challenge for valuers is to not become exposed to the vagaries inherent in simply stating that professional judgement has been applied and rationalise the basis for selecting the valuation methodology. Where possible, the valuer should look to adopt different valuation methodologies to cross-check or sense-check the valuation conclusion. 7. The valuation report was too cheap which compromised its quality. While in most commercial settings, the professional fees for the preparation of the valuation report will not be known, in litigation settings it is relatively easy to obtain this information. In some instances, it may be possible to establish that the published author of the report may have hardly worked on the report with a junior (who may not have formal professional qualifications) doing a significant bulk of the work in order to deliver a report for the quoted fees to win the job in the first place. In preparing a valuation report, there are often standard paragraphs and standard processes which can be followed which can lead to ‘cookie-cutter’ mentality by some firms offering cheaper valuation services advertising streamlined processes. All valuation reports prepared for litigation purposes will need to state compliance with court rules. With cheap reports, it’s not too difficult to find something that does not comply with court rules – usually that something is the lack of reasonable inquiries made by the valuer to support the veracity of material assumptions provided to him/her. Summary… If you are staring at a valuation report that doesn’t quite sit well with you, contact us.

This article addresses the considerations of an expert, tasked with quantifying claims for loss of profit, as part of claim for damages or compensation, as it relates to a ‘but-for’ scenario. This article also addresses the key documents that instructing plaintiff lawyers would likely need to help procure from its client to assist the expert to quantify damages.

The assessment date in the context of damages represents the point in time all of the losses, typically which may have accrued and continue to accrue over a period of time, are converted to a single number representing a ‘once-and-for-all’ lump sum amount as part of damages. This article focuses on the technical and thorny issues concerning the assessment date in damages and compensation.